Economists can’t predict the future, but economics can help improve policy today.

Oil markets aren’t the first thing that hardly anyone thinks about when reading updates on the novel coronavirus. The health threat is frightening, and the economic impact will be devastating for many low wage and service workers.

Still, the pandemic is also roiling oil and related markets in ways that will have enormous effects on economic activity and lives worldwide. At the same time, it is reminding us of economic lessons that previous shocks have taught. So now seems like a good time for a refresher.

In the oil market, small demand/supply mismatches can cause outsize price responses.

In the last month, crude oil prices have fallen nearly 40% in response to quite modest projected demand reductions and supply increases. The International Energy Agency last week revised its forecast for world crude oil demand in 2020 to be a 90,000 barrel per day (bpd) decline from 2019, from its previous estimate of about a 1 million bpd increase. That’s in a global market of 100 million bpd. Its revision to forecasted demand for later years was even smaller. Combined with a small supply increase (discussed next), that was all the revision necessary to drive a huge price drop, not just for 2020 but for years into the future. We saw the same phenomenon in 2008, 2014 and earlier price crashes.

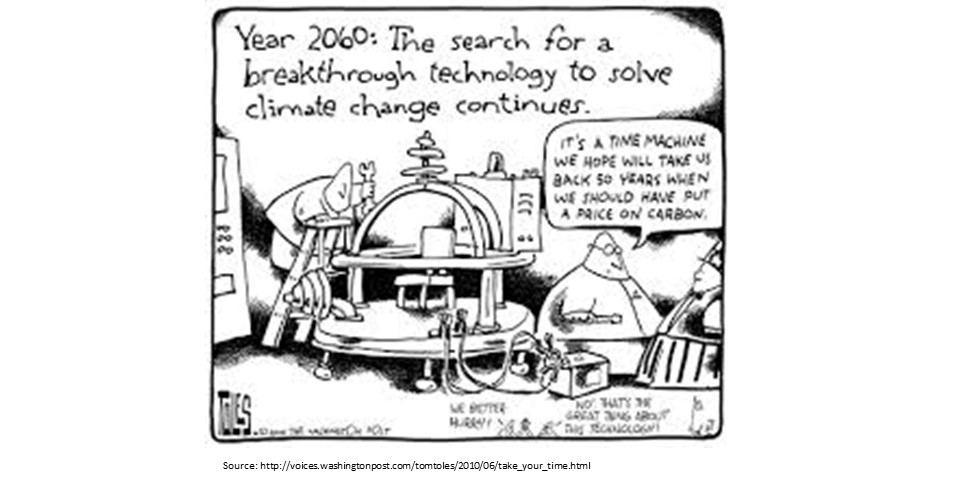

The fact that even small demand/supply mismatches can trigger big price effects is important not just for analyzing these unexpected market disruptions, but also for what they say about the challenge of fighting climate change. To make progress on reducing GHG emissions, we will need massively greater cuts to oil consumption. The last month should remind us that such cuts will almost inevitably result in very low oil prices. That makes the challenge to sustainable technologies all the greater.

OPEC is a cartel designed to undermine competition in the oil market, albeit with uneven success.

When Saudi Arabia announced a week ago that it would essentially revert to competitive behavior, that meant amping up output by only 1-3 million bpd. We’ve seen competition break out in oil markets before, for instance in 1985, 1999, 2008 and 2014. In most such cases it has taken years to put some form of effective OPEC agreement back together again.

But let’s not forget, the prices today are what a competitive oil market looks like. This is how most other commodity markets operate. The Saudis aren’t pricing below their cost or undermining the crude market. They are just departing from their usual cartel practice.

US oil producers have not been part of the cartel, but they have made very good money going along for the higher-price ride. Their investments in production capacity have been a bet that Saudi Arabia will keep restricting its own output while cajoling the other OPEC+ members to maintain “oil market stability” as the OPEC members like to call it. At least for now, that appears to be a bad bet.

Subsidizing losing companies is not likely to help workers much

The widespread bankruptcies and restructurings that will likely soon follow among US shale oil producers who banked on high prices is also part of the competitive process. Many in the industry, and some politicians, are arguing that the federal government should aide (i.e., subsidize) the industry through low-interest loans or reduced drilling royalties. They argue this is necessary to prevent widespread economic impacts to oil-producing regions, such as west Texas or North Dakota.

But unless the subsidies are huge, they are likely to have very little impact on those regional economies. Drilling new wells is expensive and much of the US activity was barely profitable when oil prices were in the $50-$60 dollar range. Unless the aid to US drillers is some form of output subsidy that offsets nearly all of the recent price decline – which could cost north of $50 billion per year — new well activity will still plummet and associated jobs will be lost.

On the other hand, once a well has been drilled it has a fairly low marginal cost of production and is seldom economic to shut down prematurely. So the subsidies generally aren’t necessary to keep them going.

Bottom line: short of massive subsidies, we would be paying oil companies to continue doing what they would have done anyway in a low-oil-price environment. Job losses would be barely affected by the subsidies. The money would just go to oil company shareholders (and executives). If the federal government did go for massive subsidies, it would prop up some drilling activity, but at a ridiculous cost per job. And as Lucas discussed last week, the cost of raising the revenue to pay those subsidies has its own job-killing impacts.

We didn’t raise tax rates on US oil producers when they were sweeping in the cash. It’s hard to see why we should start subsidizing them now that they are drowning in debt.

A unit of GHG emission or other pollutant imposes just as much cost on society when the polluter is in financial distress as when it is thriving.

The European airlines want a bailout in the form of delaying carbon pricing for them. Other industries will likely follow suit, asking for relief from environmental fees and regulations, because the economic downturn has hurt their bottom line. But their suddenly-declining profits have nothing to do with emissions costs. If governments feel the need to bail out airlines and other industries, they should do that directly and transparently, not by subsidizing the cost of the pollution they emit.

And, by the way, the price of jet fuel has plummeted in the last month by much more than any proposed new GHG price would add to their cost. The airlines’ problem is on the demand side. Their capacity, and fixed costs, adjust slowly. When the economy is booming, that leads to scarce seats and big profits. What we are seeing now is the other side of that coin.

The role of economic analysis

Policymakers sometimes express frustration with economics because it can’t provide reliable predictions about the future. But predicting the future requires knowing how all the relevant factors that will change going forward, a pretty tall order. What economics can do is help explain why markets are behaving as they are today and how specific policies are likely to change those outcomes. That won’t solve all our problems, but it sure can help keep us from making them worse.